Fourth and last step: Russia and Japan

July 29, 2008 at 8:56 pm | Posted in Language, Maps | Leave a commentTags: Ainu, aleut, alutor, asia, central, chukot, enets, ethnologue, even, evenki, forest, gilyak, itelmen, karagas, kerek, ket, koryak, languages, map, mednyj, naukan, nenets, nganasan, northern, oroch, orok, russia, selkup, siberian, southern, tundra, youkaghir, yugh, yukagir, Yupik

After some months, we finish this trip around the world with Ethnologue. We started in Alaska and Canada, passed by Greenland and Scandinavia, and now we finish in Russia and Japan. It has been a cool trip, right? Lets see what they have for Russia and Japan:

Russia (Asia) and Japan

Ainu: [ain] South Sakhalin Island and southern Kuril Islands. Dialects: Sakhalin (Saghilin), Taraika, Hokkaido (Ezo, Yezo), Kuril (Shikotan). Classification: Language Isolate Nearly extinct.

Aleut: [ale] 190 in Russia (2002 K. Matsumura). 5 on Bering Island Atkan (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 702 (1989 census). Nikolskoye settlement, Bering Island, Commander (Komandor) Islands. Alternate names: Unangany, Unangan, Unanghan. Dialects: Beringov (Bering, Atkan). Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Aleut

Aleut, Mednyj: [mud] 10 (1995 M. Krauss). Copper Island, Komandor Islands. Alternate names: Medny, Copper, Copper Island Aleut, Attuan, Copper Island Attuan, Creolized Attuan. Classification: Mixed Language, Russian-Aleut Nearly extinct.Alutor: [alr] 100 to 200 (2000 A. E. Kibrik). Ethnic population: 2,000 (1997 M. Krauss). Koryak National District, northeast Kamchatka Peninsula, many in Vyvenka village, 2 families in Rekinniki, and individual families in Tilichiki and Tymlyt. Some speakers are separated at considerable distances and without regular contact. Alternate names: Alyutor, Aliutor, Olyutor. Dialects: Alutorskij (Alutor Proper), Karaginskij (Karaga), Palanskij (Palana). Considered a dialect of Koryak until recently. Classification: Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Northern, Koryak-Alyutor

Chukot: [ckt] 10,000 (1997 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 15,000. Chukchi Peninsula, Chukot and Koryak National Okrug, northeastern Siberia. Alternate names: Chukcha, Chuchee, Chukchee, Luoravetlan, Chukchi. Dialects: Uellanskij, Pevekskij, Enmylinskij, Nunligranskij, Xatyrskij, Chaun, Enurmin, Yanrakinot. Classification: Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Northern, Chukot

Enets, Forest: [enf] 40 (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 209 with Tundra Enets (1989 census). Taimyr National Okrug. Along the Yenisei River’s lower course, upstream from Dudinka. The Forest variety is in the Potapovo settlement of the Dudinka Region. Alternate names: Yenisei Samoyedic, Bay Enets, Pe-Bae. Dialects: Forest and Tundra Enets are barely intelligible to each other’s speakers. It is transitional between Yura and Nganasan. For a time it was officially considered part of Nenets. Classification: Uralic, Samoyed Nearly extinct.

Enets, Tundra: [enh] 30 (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 209 together with Forest Enets (1990 census). Taimyr National Okrug. Along the Yenisei River’s lower course, upstream from Dudinka. ‘Tundra’ in the Vorontzovo settlement of the Ust-Yenisei Region. Alternate names: Yenisei Samoyedic, Madu, Somatu. Dialects: Tundra and Forest Enets barely intelligible to each other’s speakers. It is transitional between Yura and Nganasan. For a time it was officially considered part of Nenets. Classification: Uralic, Samoyed Nearly extinct.

Even: [eve] 7,543 (1989 census). Ethnic population: 17,199 (1989 census). Yakutia and the Kamchatka Peninsula, widely scattered over the entire Okhotsk Arctic coast. Alternate names: Lamut, Ewen, Eben, Orich, Ilqan. Dialects: Arman, Indigirka, Kamchatka, Kolyma-Omolon, Okhotsk, Ola, Tompon, Upper Kolyma, Sakkyryr, Lamunkhin. Ola dialect is not accepted by speakers of other dialects. A dialect cluster. It was incorrectly reported to be a Yukaghir dialect. Classification: Altaic, Tungus, Northern, Even

Evenki: [evn] 9,000 in Russia (1997 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 30,000 in Russia (1997 M. Krauss). Evenki National Okrug, Sakhalin Island. Capital is Ture. Alternate names: Ewenki, Tungus, Chapogir, Avanki, Avankil, Solon, Khamnigan. Dialects: Manegir, Yerbogocen, Nakanna, Ilimpeya, Tutoncana, Podkamennaya Tunguska, Cemdalsk, Vanavara, Baykit, Poligus, Uchama, Cis-Baikalia, Sym, Tokmo-Upper Lena, Nepa, Lower Nepa Tungir, Kalar, Tokko, Aldan Timpton, Tommot, Jeltulak, Uchur, Ayan-Maya, Kur-Urmi, Tuguro-Chumikan, Sakhalin, Zeya-Bureya. Classification: Altaic, Tungus, Northern, Evenki

Gilyak: [niv] 1,089 (1989 census). Population includes 100 Amur, 300 Sakhalin (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 4,673 (1989 census), including 2,000 Amur, 2,700 Sakhalin (1995 M. Krauss). Sakhalin Island, many in Nekrasovka and Nogliki villages, small numbers in Rybnoe, Moskalvo, Chir-Unvd, Viakhtu, and other villages, and along the Amur River in Aleevka village. Alternate names: Nivkh, Nivkhi. Dialects: Amur, East Sakhalin Gilyak, North Sakhalin Gilyak. The Amur and East Sakhalin dialects have difficult inherent intelligibility of each other. North Sakhalin is between them linguistically. Classification: Language Isolate

Itelmen: [itl] 60 (2000). Ethnic population: 2,481 (1989 census). Southern Kamchatka Peninsula, Koryak Autonomous District, Tigil Region, primarily in Kovran and Upper Khairiuzovo villages, west coast of the Kamchatka River. Alternate names: Itelymem, Western Itelmen, Kamchadal, Kamchatka. Dialects: Sedanka, Kharyuz, Itelmen, Xajrjuzovskij, Napanskij, Sopocnovskij. Classification: Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Southern

Karagas: [kim] 25 to 30 (2001). Ethnic population: 730 (1989 census). Siberia, Irkutsk Region. Alternate names: Tofa, Tofalar, Sayan Samoyed, Kamas, Karagass. Classification: Altaic, Turkic, Northern Nearly extinct.

Kerek: [krk] 2 (1997 M. Krauss). There were 200 to 400 speakers in 1900. Ethnic population: 400. Cape Navarin, in Chukot villages. Dialects: Mainypilgino (Majna-Pil’ginskij), Khatyrka (Xatyrskij). Previously considered a dialect of Chukot. Classification: Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Northern, Koryak-Alyutor Nearly extinct.

Ket: [ket] 550 to 990 (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 1,222 (2000). Upper Yenisei Valley, Krasnoyarski krai, Turukhansk, and Baikitsk regions, Sulomai, Bakhta, Verkhneimbatsk, Kellog, Kangatovo, Surgutikha, Vereshchagino, Baklanikha, Farkovo, Goroshikha, and Maiduka villages. East of the Khanti and Mansi, eastern Siberia. Alternate names: Yenisei Ostyak, Yenisey Ostiak, Imbatski-Ket. Classification: Yeniseian

Koryak: [kpy] 3,500 (1997 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 7,000. Koryak National Okrug, south of the Chukot; northern half of Kamchatka Peninsula and adjacent continent. Alternate names: Nymylan. Dialects: Cavcuvenskij (Chavchuven), Apokinskij (Apukin), Kamenskij (Kamen), Xatyrskij, Paren, Itkan, Palan, Gin. Chavchuven, Palan, and Kamen are apparently not inherently intelligible. Classification: Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Northern, Koryak-Alyutor

Nenets: [yrk] 26,730 (1989 census). Population includes 1,300 Forest Nenets, 25,000 Tundra Nenets. Ethnic population: 34,665 (1989 census) including 2,000 Forest Enets. Northwest Siberia, tundra area from the mouth of the northern Dvina River in northeastern Europe to the delta of the Yenisei in Asia, and a scattering on the Kola Peninsula; Nenets, Yamalo-Nenets, and Taimyr national okrugs. Alternate names: Nenec, Nentse, Nenetsy, Yurak, Yurak Samoyed. Dialects: Forest Yurak, Tundra Yurak. Classification: Uralic, Samoyed

Nganasan: [nio] 500 (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 1,300. Taimyr National Okrug, Taimyr Peninsula, Siberia, Ust-Avam village in the Dudinka Region; Volochanka and Novaya villages in the Khatang Region. They are the northernmost people in Russia, near the Yakut, Dolgan, and Evenki peoples. Alternate names: Tavgi Samoyed. Dialects: Avam, Khatang. Classification: Uralic, Samoyed

Oroch: [oac] 100 to 150 (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 900 (1990 census). Eastern Siberia in the Khabarovsk Krai along the rivers that empty into the Tatar Channel, on Amur River not far from the city of Komsomolsk-na-Amure. Many live in the Vanino Region in Datta and Uska-Orochskaya settlements. Some live among the Nanai. Alternate names: Orochi. Dialects: Kjakela (Kjakar, Kekar), Namunka, Orichen, Tez. Classification: Altaic, Tungus, Southern, Southeast, Udihe

Orok: [oaa] 30 to 82 in Russia (1995 M. Krauss). Population total all countries: 33 to 85. Ethnic population: 250 to 300 (1995 M. Krauss). Sakhalin Island, Poronajsk District, Poronajsk town, Gastello and Vakhrushev settlements; Nogliki District, Val village, Nogliki settlement. Also spoken in Japan. Alternate names: Oroc, Ulta, Ujlta, Uilta. Dialects: Poronaisk (Southern Orok), Val-Nogliki (Nogliki-Val, Northern Orok). Significant differences between dialects. For a while Orok was officially considered part of Nanai. Classification: Altaic, Tungus, Southern, Southeast, Nanaj Nearly extinct.

Selkup: [sel] 1,570 (1994 Salminen, 1994 Janhunen). Northern Sel’kup has 1,400 speakers out of 1,700, Central Sel’kup has 150 speakers out of 1,700, Southern Sel’kup has 20 speakers out of 200. Ethnic population: 3,600. Tom Oblast, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District, Krasnoyarski Krai and Tomskaya Oblast. The northern dialect is spoken in Krasnoselkup Region, Krasnoselkup, Sidorovsk, Tolka, Ratta, and Kikiyakki villages; part of the Purovsk Region, Tolka Purovskaya village; adjacent regions of the Krasnoyarski Krai; Kureika village, Kellog, and Turukhan River basin and Baikha. The southern dialect (Tym) is spoken in a range of villages in the northern part of the Tomskaya Oblast. Alternate names: Ostyak Samoyed. Dialects: Taz (Northern Sel’kup, Tazov-Baishyan), Tym (Central Selk’up, Kety), Narym (Central Sel’kup), Srednyaya Ob-Ket (Southern Sel’kup). A dialect continuum with difficult or impossible intelligibility between the extremes. Speakers in the south are separated from others. Classification: Uralic, Samoyed

Yugh: [yuu] 2 or 3 (1991 G. K. Verner in Kibrik). Nonfluent speakers. Ethnic population: 10 to 15 (1991 G. K. Verner in Kibrik). Turukhan Region of the Krasnoyarsk Krai at the Vorogovo settlement. Previously they lived along the Yenisei River from Yeniseisk to the mouth of the Dupches. Alternate names: Yug. Classification: Yeniseian Nearly extinct.

Yukaghir, Northern: [ykg] 30 to 150 (1995 M. Krauss, 1989 census). Ethnic population: 230 to 1,100 (1995 M. Krauss, 1989 census). Yakutia and the Kamchatka Peninsula. Alternate names: Yukagir, Jukagir, Odul, Tundra, Tundre, Northern Yukagir. Dialects: Distinct from Southern Yukaghir (Kolyma). It may be distantly related to Altaic or Uralic. Classification: Yukaghir Nearly extinct.

Yukaghir, Southern: [yux] 10 to 50 (1995 M. Krauss, 1989 census). Ethnic population: 130 (1995 M. Krauss, 1989 census). Yakutia and the Kamchatka Peninsula. Alternate names: Yukagir, Jukagir, Odul, Kolyma, Kolym, Southern Yukagir. Dialects: Not inherently intelligible with Northern Yukaghir. Classification: Yukaghir Nearly extinct.Yupik, Central Siberian: [ess] 300 in Russia (1991 Kibrik). Ethnic population: 1,200 to 1,500 in Russia (1991 Kibrik). Chukchi National Okrug, coast of the Bering Sea, Wrangel Island. The Chaplino live in Providenie Region in Novo-Chaplino and Providenie villages. Alternate names: Yoit, Yuk, Yuit, Siberian Yupik, “Eskimo”, Bering Strait Yupik, Asiatic Yupik. Dialects: Aiwanat, Noohalit (Peekit), Wooteelit, Chaplino. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Yupik, Siberian

Yupik, Naukan: [ynk] 75 (1990 L.D. Kaplan). Ethnic population: 350. Chukota Region, Laurence, Lorino, and Whalen villages, scattered. Formerly spoken in Naukan village and the region surrounding East Cape, Chukot Peninsula, but they have been relocated. Alternate names: Naukan, Naukanski. Dialects: 60% to 70% intelligibility of Chaplino. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Yupik, Siberian.

The situation is quite depressing, with a lot of languages that are tagged as “nearly extinct”… Here you have, as usually, the map for the zone. As Russia is a huge country, Ethnologue has one general index map, which I am showing here, and then some more detailed maps, that you can find clicking here:

Native people of Kamchatka

July 29, 2008 at 1:39 pm | Posted in Maps, Naming, Siberia | Leave a commentTags: aleut, chavchuvens, chukcis, evenki, evenky, evens, History, itelmens, kamchatka, koryaks, lamuts, nimilans, nimilany, orochi, peninsula, russia

Some times you find out information in a weird way, as it happened to me last week. I was finding material fot the blog, and I ended up in a website with information of the native people of Kamchatka, a big big island in Russia. The surpising thing for me was that the site was owned by a travel agency! Anyway, it was a good starting, this is what they say:

Koryaks

The Koryaks are the main population of the northern Kamchatka part. They have their own autonomy – the Koryaksky Region. The name of this people as Krasheninnikov and Steller thought originated from “khora” – “deer”. But Kryaks don’t call themselves with this word. The coastal residents call themselves as “nimilany” – “residents of a settled village”. Nomads herding deer called themselves “chavchuvens“, it means “reindeer people”.

For the Chavchuvens reindeer breading was the main, even the only way of living. Deer gave them everything necessary: meat, skin for clothes (reindeer skin for coveralls, footwear) and for building of thansportable dwellings (yarangas), bones were used for making tools and household articles, fat – for dwelling lightening. Deer were a means of conveyance either.

For the Nimilans the main way to survive was fishing. Fish was generally caught in rivers with the help of stinging-nettle (it took about two years to make one net and it was used only for one year). In settled villages marine hunting was the second way of surviving after fishing. Going out to sea on skin covered baydarkas was common. Harbor seal and whales became the target of harpoons, which were tied to the bow, and were killed with stone tip spears. Marine animals, skin was used for boat, ski covering, footwear, bags, sacks and belts. Domestic activities were highly developed – wood and bone carving, metal works, national clothes and carpets making, embroiling with beads, braiding. A lot of such works are displayed at the Museum of Local Lore. Tourists can admire the skillfulness of the masters. The Nimilans lived in groups: in winter – in half-dug-houses, in summer – in booths with their families, they used to catch fish, to hunt, and to pick berries. The Chavchuvens lived in temporary settlements consisting of some skin-covered yarangs. They used to herd reindeer and to dress skin. Hunting and fishing were of the secondary value for them. They migrated on dog- and reindeer-sledges.

Itelmens

The name of the nationality means “living here”. The south bound of settling is the Lopatka Cape. Northern one – the Tigil River on the west coast, the Uka River is on the east coast. Ancient Itlmen settlements were located on the banks of the Kamchatka (Uykoal), Yelovka (Kooch), Bolshaya, Bistraya, Avacha rivers and on the Avacha Harbor coast.

At the end of the 17 – beginning of the 18 centuries, when Russian explorers crossed the central part of Kamchatka, the Itelmens were at the level of disintegration primitive communal system development.

At the settlement consisting of a few half-dug-houses the folk Toyony lived. Some names of Toytony are written on the of Kamchatka. Itelmens life in summer was spent near some water resources and on them. They moved along the rivers in whole-carved boats made mainly of poplar. They caught fish with threshed nettle nets, built trapping dams. Some fish was cooked as yukola, some was burried for some time under the ground. But lack of salt didn’t allow to store much fish.Hunting was of the same value for this folk – fox, sable, bear, snow sheep; at the coast area – marine animals: sea lion, seal, sea otter. Also gathering was very popular (edible roots, edible and officinal plants, berries). Means of conveyance were made of birch (sledge and cargo sledge with soft belts). The ancient sledges were richly decorated.

The Itelmens ate a lot of fish, preferred baked one (chuprikh) and fish cakes “telno”, they ate young sprouts and runners of Filepinolium Maxim, Heracleum Dulse Fish (processed and ate them only after they acquired stinging power); as a medicine against scurvy they used cedar cones with dry salmon caviar chasing this mixture with tea. Food was seasoned with fat – favorite spice of all northern peoples. Women-Itelmens had a custom to wear wigs. Those who had the most luxurious and the thickest one was highly honored. Those fashionable women never wore hats. Young women did up their heavy black raven-wing-like hair in lot of thin plaits decorating them with small hair wigs in the shape of hats. Perhaps, that’s why the Chukchis and Koryaks might have called the Itelmens kamchadals, because in both languages the word “kamcha” means “curly”, “disheveled”, and “levit” or “lyavit” means “head”.

Itelmens clothes were extraordinary, they were made of sable, fox, snow sheep, dog’s skin with numerous ermine tassels and fluffy edged sleeves, hood, collar and hem. Steller wrote: “:the most beautiful reindeer skin coveralls (kukhlyankas) were decorated on the collars, sleeves and hems with dog’s fur, and on the kaftan (short reindeer skin coverall) was hanged with hundreds of seal’s tassels coloured red, they dangled to and fro at every movement”. Such Itelmens’ clothing made an impression of hairiness.

Evens and Evenky (tunguses)

The Evens and Evenky (tunguses) are similar by culture. The Evens ancestors having come to Kamchatka changed their traditional occupation hunting for reindeer breeding. Russians arriving to Kamchatka called the Evens roaming from place to place along the Okhotsk seaside “lamuts”, it means “living by the sea”. Herdsmen they called “orochi”, it means “reindeer men”. Beside reindeer breeding and hunting the coastal Evens caught fish and hunted marine animals. For fishing they made different kinds of dams and traps. Blacksmith’s work was very popular with the Evens.

The Evens did not wear blind clothes like the Koryaks, Itelmens and Chukcis did, but unlacing ones. Complete set of a man’s wear consisted of a short knee-reaching reindeer parka with running down lapels, trousers, a chest apron put on the parka, knee protectors, furstockings and boots made of reindeer led skin with soles of bearded seal skin. Wearing especially women’s one was decorated with beads. In contrast to other natives of Kamchatka the Evens didn’t use dogsleds and didn’t wear blind clothes.

Chukchis

The Northern Koryaks’ neighbours were the Chukchis, “reindeer men” (chauchu), some of them moved to Kamchatka. As for the household the Chukchi were like the Koryaks – reindeer breeders. A holder of less than 100 reindeer was considered poor and couldn’t keep a herd. Unfortunately, history of these two peoples’ neighbourhood knows a lot of examples of wars for herds. The Chukchis are native Kamchatka people, now a lot of them live here. Like the Koryaks there were the Chukchis who lived in settled villages and provided their living by fishing and hunting for marine animals. The Chukchis are perfect seamen skillfully operating boats on a cold sea. It is well known that their “fleet” used to trade with the Eskimoes launching towards the American shore. Main hunting implements were a bow and arrows, a spear and a harpoon. A bow and a spear were used in hunting for wild reindeer and snow sheep, a harpoon and a lance – in marine hunting. Arrow-, spear- and harpoon-heads were made of bone and stone. In catching all water-fowl and game the Chukchis used bola (an instrument for catching birds on the wing) and pratsha (a military weapon either). The protection armour was made of antlers, walrus’ skin and tusks. Main Chukchis‘ means of conveyance was reindeer, but like the Koryaks and Itelmens they also used dogsledges. On the sea the Chukchis moved in kayaks accommodating 20-30 men. With favorable wind they used square sails made of reindeer suede (rovdugas) like the Koryaks–Nimilans, and for a better balance they tied to board sides stocking-like sealskin, which was filled with air.

Aleuts

The Aleuts – ancient Aleutian Islands natives. They called themselves “unangan”, it means “seaside residents”. Main traditional Aleuts‘ occupations were hunting for marine animals and fishing. For winter the Aleuts stored eggs from birds colonies on the seashore.

The dwellings of the Aleuts were similar to the traditional half-dughouses but slightly different. Among the household articles there were baskets, bags plaited from grass; for storing of fat, yukola, crowberries with fat and so on dry seal stomach was used. On the Bering Island dogsleds became a very popular means of conveyance. For wandering in the mountains the Aleuts of the Medny Island used broad skis covered with seal skin for the nap would help while climbing not to slide down from the mountain.

Did you read that? Aleut people in Kamchatka! I find this connection amazing. I am reading a book about genetics, if I finish it some day – I will, I will… – I will summarize the main information related to this blog. Anyway, I also searched a bit about Kamchatka, as, to be honest, I did not now almost anything about it! So thanks to the Wiki, here you have some facts:

Illustration from Stepan Krasheninnikov’s Account of the Land of Kamchatka (1755).

The Kamchatka Peninsula (Russian: полуо́стров Камча́тка) is a 1,250-kilometer long peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of 472,300 km². It lies between the Pacific Ocean to the east and the Sea of Okhotsk to the west.[1] Immediately offshore along the Pacific coast of the peninsula runs the 10,500 meter deep Kuril-Kamchatka Trench.

[…] Muscovite Russia claimed the Kamchatka Peninsula in the 17th century. Ivan Kamchaty, Simon Dezhnev, the Cossack Ivan Rubets and other Russian explorers made exploratory trips to the area during the reign of Tsar Alexis, and returned with tales of a land of fire, rich with fish and fur.

In 1697, Vladimir Atlasov, founder of the Anadyr settlement, led a group of 65 Cossacks and 60 Yukaghir natives to investigate the peninsula. He built two forts along the Kamchatka River which became trading posts for Russian fur trappers. From 1704 to 1706, they settled the Cossack colonies of Verkhne- (upper) and Nizhne- (lower) Kamchatsky. Far away from the eye of their masters, the Cossacks mercilessly ruled the indigenous Kamchadal.

Excesses were such that the North West Administration in Yakutsk sent Atlasov with the authority (and the cannons) to restore government order, but it was too late. The local Cossacks had too much power in their own hands and in 1711 Atlasov was killed. From this time on, Kamchatka became a self-regulating region, with minimal interference from Yakutsk.

By 1713, there were approximately five hundred Cossacks living in the area. Uprisings were common, the largest being in 1731 when the settlement of Nizhnekamchatsky was razed and its inhabitants massacred. The remaining Cossacks regrouped and, reinforced with firearms and cannons, were able to put down the rebellion.

The Second Kamchatka Expedition by the Danish explorer Vitus Bering, in the employ of the Russian Navy, began the “opening” of Kamchatka in earnest, helped by the fact that the government began to use the area as a place of exile. In 1755, Stepan Krasheninnikov published the first detailed description of the peninsula, An Account of the Land of Kamchatka. The Russian government encouraged the commercial activities of the Russian-American Company by granting land to newcomers on the peninsula. By 1812, the indigenous population had fallen to fewer than 3,200, while the Russian population had risen to 2,500.

In 1854, the French and British, who were battling Russian forces on the Crimean Peninsula, attacked Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. During the Siege of Petropavlovsk, 988 men with a mere 68 guns managed successfully to defend the outpost against 6 ships with 206 guns and 2,540 French and British soldiers. Despite the heroic defense, Petropavlovsk was abandoned as a strategic liability after the Anglo-French forces withdrew. The next year when a second enemy force came to attack the port, they found it deserted. Frustrated, the ships bombarded the city and withdrew.

The next fifty years were lean ones for Kamchatka. The military naval port was moved to Ust-Amur and in 1867 Alaska was sold to the United States, making Petropavlovsk obsolete as a transit point for traders and explorers on their way to the American territories. In 1860, Primorsky (Maritime) Region was established and Kamchatka was placed under its jurisdiction. In 1875, the Kuril Islands were ceded to Japan in return for Russian sovereignty over Sakhalin. The Russian population of Kamchatka stayed around 2,500 until the turn of the century, while the native population increased to 5,000.

World War II hardly affected Kamchatka except for its service as a launch site for the invasion of the Kurils in late 1945. After the war, Kamchatka was declared a military zone. Kamchatka remained closed to Russians until 1989 and to foreigners until 1990.

Well, it seems that this project is getting bigger and bigger, and the more I learn the less I know! A lot of job for the summer I guess 😉

Deepening in Alaska indigenous languages

July 26, 2008 at 2:38 pm | Posted in Language, Naming | Leave a commentTags: ahtna, Alaska, aleut, alutiiq, center, central yup'ik, definition, deg hit'an, dena'ina, eyak, fairbanks, gwich'in, haida, hän, holikachuk, iñupiaq, iingit, koyukon, Language, languages, map, Naming, Research, siberian yupik, tanacross, tanana, Terminology, tsimshian, university, upper kuskokwim, upper tanana

Few months ago I promised to deepen in the Alaska Native Languages Center of the University of Alaska Fairbanks. So did I, and I listed all the languages they describe ont heir site:

Aleut: Unangax^ (Aleut) is one branch of the Eskimo-Aleut language family. Its territory in Alaska encompasses the Aleutian Islands, the Pribilof Islands, and the Alaska Peninsula west of Stepovak Bay. Unangax^ is a single language divided at Atka Island into the Eastern and the Western dialects. Of a population of about 2,200 Unangax^, about 300 speak the language. This language was formerly called Aleut, a general term for introduced by Russian explorers and fur traders to refer to Native Alaskan of the Aleutian Islands, the Alaska Peninsula, Kodiak Island, and Prince William Sound (see the section on the Alutiiq language). The term Unangax^ means ‘person’ and probably derives from the root una, which refers to the seaside. The plural form ‘people’ is pronounced Unangas in the western dialect and Unangan in the eastern dialect, and these terms are also sometimes used to refer to the language. The indigenous term for the language is Unangam

Alutiiq: Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) is a Pacific Gulf variety of Yupik Eskimo spoken in two dialects from the Alaska Peninsula to Prince William Sound, including Kodiak Island. Of a total population of about 3,000 Alutiiq people, about 400 still speak the language. Although traditionally the people called themselves Sugpiaq (suk ‘person’ plus -piaq ‘real’), the name Alutiiq was adopted from a Russian plural form of Aleut, which Russian invaders applied to the Native people they encountered from Attu to Kodiak. Closely related to Central Alaskan Yup’ik, the Alutiiq language is divided into the Koniag and the Chugach dialects. Koniag Alutiiq is spoken on the upper part of the Alaska Peninsula and Kodiak Island (and Afognak Island before it was deserted following the 1964 earthquake). Chugach Alutiiq is spoken on the Kenai Peninsula from English Bay and Port Graham to Prince William Sound where it meets Eyak. The first work on Alutiiq literacy was done by Russian Orthodox monks Herman and Gideon and the talented student Chumovitski, although their progress continued only until about 1807 and almost none of their work survives. After that, a few others – notably Tyzhnov, Uchilishchev, and Zyrianov – worked on the language during the Russian period, producing a translation of Matthew, a Catechism, and primer, but they achieved less success than those who worked in Aleut. The first modern linguistic work on Alutiiq was done by Irene Reed in the early 1960s and by Jeff Leer beginning in 1973. Leer has produced both a grammar and a dictionary of Koniag Alutiiq for classroom use.

Ahtna: Ahtna Athabascan is the language of the Copper River and the upper Susitna and Nenana drainages in eight communities. The total population is about is about 500 with perhaps 80 speakers. The first extensive linguistic work on Ahtna was begun in 1973 by James Kari, who published a comprehensive dictionary of the language in 1990.

Central Alaskan Yup’ik: Central Alaskan Yup’ik lies geographically and linguistically between Alutiiq and Siberian Yupik. The use of the apostrophe in Central Alaskan Yup’ik, as opposed to Siberian Yupik, denotes a long p. The word Yup’ik represents not only the language but also the name for the people themselves (yuk ‘person’ plus pik ‘real’.) Central Alaskan Yup’ik is the largest of the state’s Native languages, both in the size of its population and the number of speakers. Of a total population of about 21,000 people, about 10,000 are speakers of the language. Children still grow up speaking Yup’ik as their first language in 17 of 68 Yup’ik villages, those mainly located on the lower Kuskokwim River, on Nelson Island, and along the coast between the Kuskokwim River and Nelson Island. The main dialect is General Central Yup’ik, and the other four dialects are Norton Sound, Hooper Bay-Chevak, Nunivak, and Egegik. In the Hooper Bay-Chevak and Nunivak dialects, the name for the language and the people is “Cup’ik” (pronounced Chup-pik). Early linguistic work in Central Yup’ik was done primarily by Russian Orthodox, then Jesuit Catholic and Moravian missionaries, leading to a modest tradition of literacy used in letter writing. In the 1960s, Irene Reed and others at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks developed a modern writing system for the language, and their work led to the establishment of the state’s first school bilingual programs in four Yup’ik villages in the early 1970s. Since then a wide variety of bilingual materials has been published, as well as Steven Jacobson’s comprehensive dictionary of the language and his complete practical classroom grammar, and story collections and narratives by many others including a full novel by Anna Jacobson.

Deg Xinag: Deg Xinag (also Deg Hit’an; formerly known by the pejorative Ingalik) is the Athabascan language of Shageluk and Anvik and of the Athabascans at Holy Cross below Grayling on the lower Yukon River. Of a total population of about 275 Ingalik people, about 40 speak the language. A collection of traditional folk tales by the elder Belle Deacon was published in 1987, and a literacy manual in 1993.

Dena’ina: Dena’ina (Tanaina) is the Athabascan language of the Cook Inlet area with four dialects on the Kenai Peninsula, Upper Inlet area above Anchorage, and coastal and inland areas of the west side of Cook Inlet. Of the total population of about 900 people, about 75 speak the language. James Kari has done extensive work on the language since 1972, including his edition with Alan Boraas of the collected writings of Peter Kalifornsky in 1991.

Eyak: Eyak is not an Athabascan language, but a coordinate sub-branch to Athabascan as a whole in the Athabascan-Eyak branch of the Athabascan-Eyak-Tlingit language family. Eyak was spoken in the 19th century from Yakutat along the southcentral Alaska coast to Eyak at the Copper River delta, but by the 20th century only at Eyak. It is now represented by about 50 people but no surviving fluent speakers.only one remaining speaker, born in 1920 and living in Anchorage. Comprehensive documentation of Eyak has been carried out since the 1960s by Michael Krauss, including his edition of traditional stories, historic accounts, and poetic compositions by Anna Nelson Harry. The name Eyak itself is not an Eyak word but instead derives from the Chugach Eskimo name (Igya’aq) of the Eyak village site near the mouth of Eyak River (Krauss 2006:199). The Chugach word Igya’aq is a general term referring to ‘the outlet of a lake into a river.’

With the passing of Marie Smith Jones (pictured above with linguist Michael Krauss) on January 21, 2008 Eyak became the first Alaska Native language to become extinct in recent history.Gwich’in: Gwich’in (Kutchin) is the Athabascan language spoken in the northeastern Alaska villages of Arctic Village, Venetie, Fort Yukon, Chalkyitsik, Circle, and Birch Creek, as well as in a wide adjacent area of the Northwest Territories and the Yukon Territory. The Gwich’in population of Alaska is about 1,100, and of that number about 300 are speakers of the language. Gwich’in has had a written literature since the 1870s, when Episcopalian missionaries began extensive work on the language. A modern writing system was designed in the 1960s by Richard Mueller, and many books, including story collections and linguistic material, have been published by Katherine Peter, Jeff Leer, Lillian Garnett, Kathy Sikorski, and others.

Haida: Haida (Xa’ida) is the language of the southern half of Prince of Wales Island in the villages of Hyadaburg, Kasaan, and Craig, as well as a portion of the city of Ketchikan. About 600 Haida people live in Alaska, and about 15 of the most elderly of those speak the language. Haida is considered a linguistic isolate with no proven genetic relationship to any language family. A modern writing system was developed in 1972.

Han: Hän is the Athabascan language spoken in Alaska at the village of Eagle and in the Yukon Territory at Dawson. Of the total Alaskan Hän population of about 50 people, perhaps 12 speak the language. A writing system was established in the 1970s, and considerable documentation has been carried out at the Alaska Native Language Center as well as at the Yukon Native Language Centre in Whitehorse.

Holikachuk: Holikachuk is the Athabascan language of the Innoko River, formerly spoken at the village of Holikachuk, which has moved to Grayling on the lower Yukon River. Holikachuk, which is intermediate between Ingalik and Koyukon, was identified as a separate language in the 1970s. The total population is about 200, and of those perhaps 12 speak the language.

Inupiaq:Inupiaq is spoken throughout much of northern Alaska and is closely related to the Canadian Inuit dialects and the Greenlandic dialects, which may collectively be called “Inuit” or Eastern Eskimo, distinct from Yupik or Western Eskimo. Alaskan Inupiaq includes two major dialect groups ? North Alaskan Inupiaq and Seward Peninsula Inupiaq. North Alaskan Inupiaq comprises the North Slope dialect spoken along the Arctic Coast from Barter Island to Kivalina, and the Malimiut dialect found primarily around Kotzebue Sound and the Kobuk River. Seward Peninsula Inupiaq comprises the Qawiaraq dialect found principally in Teller and in the southern Seward Peninsula and Norton Sound area, and the Bering Strait dialect spoken in the villages surrounding Bering Strait and on the Diomede Islands. Dialect differences involve vocabulary and suffixes (lexicon) as well as sounds (phonology). North Slope and Malimiut are easily mutually intelligible, although there are vocabulary differences (tupiq means ?tent? in North Slope and ?house? in Malimiut; iglu is ?house? in North Slope) and sound differences (?dog? is qimmiq in North Slope and qipmiq in Malimiut). Seward Peninsula and North Alaskan dialects differ significantly from each other, and a fair amount of experience is required for a speaker of one to understand the dialect of the other. The name “Inupiaq,” meaning “real or genuine person” (inuk ?person? plus -piaq ?real, genuine?), is often spelled “Iñupiaq,” particularly in the northern dialects. It can refer to a person of this group (“He is an Inupiaq”) and can also be used as an adjective (“She is an Inupiaq woman”). The plural form of the noun is “Inupiat,” referring to the people collectively (“the Inupiat of the North Slope”). Alaska is home to about 13,500 Inupiat, of whom about 3,000, mostly over age 40, speak the language. The Canadian Inuit population of 31,000 includes about 24,000 speakers. In Greenland, a population of 46,400 includes 46,000 speakers.

Koyukon: Koyukon occupies the largest territory of any Alaskan Athabascan language. It is spoken in three dialects – Upper, Central, and Lower – in 11 villages along the Koyukuk and middle Yukon rivers. The total current population is about 2,300, of whom about 300 speak the language. The Jesuit Catholic missionary Jules Jette did extensive work on the language from 1899-1927. Since the early 1970s, native Koyukon speaker Eliza Jones has produced much linguistic material for use in schools and by the general public.

Siberian Yupik / St. Lawrence Island Yupik: Siberian Yupik (also St. Lawrence Island Yupik) is spoken in the two St. Lawrence Island villages of Gambell and Savoonga. The language of St. Lawrence Island is nearly identical to the language spoken across the Bering Strait on the tip of the Siberian Chukchi Peninsula. The total Siberian Yupik population in Alaska is about 1,100, and of that number about 1,050 speak the language. Children in both Gambell and Savoonga still learn Siberian Yupik as the first language of the home. Of a population of about 900 Siberian Yupik people in Siberia, there are about 300 speakers, although no children learn it as their first language. Although much linguistic and pedagogical work had been published in Cyrillic on the Siberian side, very little was written for St. Lawrence Island until the 1960s when linguists devised a modern orthography. Researchers at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks revised that orthography in 1971, and since then a wide variety of curriculum materials, including a preliminary dictionary and a practical grammar, have become available for the schools. Siberian Yupik is a distinct language from Central Alaskan Yup’ik. Notice that the former is spelled without an apostrophe.

(Lower) Tanana: Tanana Athabascan is now spoken only at Nenana and Minto on the Tanana River below Fairbanks. The Athabascan population of those two villages is about 380, of whom about 30, the youngest approaching age 60, speak the language. Michael Krauss did the first major linguistic fieldwork on this language beginning in 1961, and this was continued by James Kari. Recent publications in the language include the 1992 edition of stories told by Teddy Charlie as recorded by Krauss in 1961, and a preliminary dictionary compiled by Kari in 1994.

Tanacross Athabascan: Tanacross is the ancestral language of the Mansfield-Ketchumstock and Healy Lake-Jospeph Village bands. It is spoken today at Healy Lake, Dot Lake, and Tanacross on the middle Tanana River. The total population is about 220, of whom about 65 speak the language. A practical alphabet was established in 1973 and a few booklets have been published at the Alaska Native Language Center, but Tanacross remains one of the least documented of Alaska Native languages.

(Upper) Tanana: Upper Tanana Athabascan is spoken mainly in the Alaska villages of Northway, Tetlin, and Tok, but has a small population also across the border in Canada. The Alaskan population is about 300, of whom perhaps 105 speak the language. During the 1960s, Paul Milanowski established a writing system, and he worked with Alfred John to produce several booklets and a school dictionary for use in bilingual programs.

Tlingit: Tlingit (Łingít) is the language of coastal Southeastern Alaska from Yakutat south to Ketchikan. The total Tlingit population in Alaska is about 10,000 in 16 communities with about 500 speakers of the language. Tlingit is one branch of the Athabascan-Eyak-Tlingit language family. A practical writing system was developed in the 1960s, and linguists such as Constance Naish, Gillian Story, Richard and Nora Dauenhauer, and Jeff Leer have documented the language through a number of publications, including a verb dictionary, a noun dictionary, and a collection of ancient legends and traditional stories by Tlingit elder Elizabeth Nyman.

Tsimshian: Tsimshian has been spoken at Metlakatla on Annette Island in the far southeastern corner of Alaska since the people moved there from Canada in 1887 under the leadership of missionary William Duncan. Currently, of the 1,300 Tsimshian people living in Alaska, not more than 70 of the most elderly speak the language. Franz Boas did extensive research on the language in the early 1900s, and in 1977 the Metlakatlans adopted a standard practical orthography for use also by the Canadian Coast Tsimshians.

Tunuu: although the early Russian fur trade was exploitative and detrimental to the Aleut population as a whole, linguists working through the Russian Orthodox Church made great advances in literacy and helped foster a society that grew to be remarkably bilingual in Russian and Unangax^. The greatest of these Russian Orthodox linguists was Ivan Veniaminov who, beginning in 1824, worked with Aleut speakers to develop a writing system and translate religious and educational material into the native language. In modern times the outstanding academic contributor to Unangax^ linguistics is Knut Bergsland who from 1950 until his death in 1998 worked with Unangax^ speakers such as William Dirks Sr. and Moses Dirks – now himself a leading Unangax^ linguist – to design a modern writing system for the language and develop bilingual curriculum materials including school dictionaries for both dialects. In 1994 Bergsland produced a comprehensive Unangax^ dictionary, and in 1997 a detailed reference grammar.

Upper Kuskokwim: Upper Kuskokwim Athabascan is spoken in the villages of Nikolai, Telida, and McGrath in the Upper Kuskokwim River drainage. Of a total population of about 160 people, about 40 still speak the language. Raymond Collins began linguistic work at Nikolai in 1964, when he established a practical orthography. Since then he has worked with Betty Petruska to produce many small booklets and a school dictionary for use in the bilingual program.

I have to compare this list of languages with the one provided by Ethnologue, but in case of non-coincidence I think that the ANLC is more reliable, as they work shoulder to shoulder with them.

Meeting the Aleutians

July 13, 2008 at 11:09 pm | Posted in Alaska, Naming | Leave a commentTags: Alaska, aleut, History, islands, people

After another long break – not my choice, for sure – I’ll try to continue with this huge and quite impossible project. I was reading I don’t know what on the Internet and I ended up in the Wikipedia page for the entry “aleut”. Their lands remind my a “tail” of an exotic animal, just where Alaska finishes. You can see that in the map of this older entry. It would be amazing to travel there! This is what I found out:

The Aleuts

The Aleuts (self-denomination: Unangax̂, Unangan or Unanga) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska, United States and Kamchatka Krai, Russia. The homeland of the Aleuts includes the Aleutian Islands, the Pribilof Islands, the Shumagin Islands, and the far western part of the Alaska Peninsula. During the 19th century, the Aleuts were deported from the Aleutian Islands to the Commander Islands (now part of Kamchatka Krai) by the Russian-American Company.

History

After the arrival of missionaries in the late 18th century, many Aleuts became Christian by joining the Russian Orthodox Church. One of the earliest Christian martyrs in North America was Saint Peter the Aleut.

In 18th century, Russian furriers established settlements on the islands and exploited the people. (See Early history)

There was a recorded revolt against Russian workers in Amchitka in 1784. It started from the exhaustion of necessities that the Russians provided to local people in return for furs they had made. (See: Aleuts’ revolt)

In 1811, Aleuts went to San Nicholas to hunt. There was argument over paying the Nicoleño for being allowed to hunt on their island, a battle began almost all of the native men were killed. By 1853, only one native was left. (See Island of the Blue Dolphins)

Prior to major influence from outside, there were approximately 25,000 Aleuts on the archipelago. Barbarities by outside corporations and foreign diseases eventually reduced the population to one-tenth this number. Further declines led to a 1910 Census count of 1,491 Aleuts.

In 1942, during World War 2, Japanese forces occupied Attu and Kiska Islands in the western Aleutians, and later transported captive Attu Islanders to Hokkaidō, where they were held as prisoners of war. Hundreds more Aleuts from the western chain and the Pribilofs were evacuated by the United States government during WW2 and placed in internment camps in southeast Alaska, where many died. The Aleut Restitution Act of 1988 was an attempt by Congress to compensate the survivors.

The World War II campaign to retake Attu and Kiska was a significant component of the operations of the Asian theater.

Culture

Aleuts constructed partially underground houses called barabaras. According to Lillie McGarvey, a 20th-century Aleut leader, barabaras keep “occupants dry from the frequent rains, warm at all times, and snugly sheltered from the high winds common to the area”.

Traditional arts of the Aleuts include hunting, weapon-making, building of baidarkas (special hunting boats), and weaving. 19th century craftsmen were famed for their ornate wooden hunting hats, which feature elaborate and colorful designs and may be trimmed with sea lion whiskers, feathers, and ivory. Aleut seamstresses created finely stitched waterproof parkas from seal gut, and some women still master the skill of weaving fine baskets from rye and beach grass.

Aleut basketry is some of the finest in the world, and the tradition began in prehistoric times. Early Aleut women created baskets and woven mats of exceptional technical quality using only an elongated and sharpened thumbnail as a tool. Today, Aleut weavers continue to produce woven pieces of a remarkable cloth-like texture, works of modern art with roots in ancient tradition. The Aleut term for grass basket is qiigam aygaaxsii.

Language

While English and Russian are the dominant languages used by Aleuts living in the US and Russia respectively, the Aleut language is still spoken by several hundred people. The language belongs to the Eskimo-Aleut language family and includes three dialect groupings: Eastern Aleut, spoken on the Eastern Aleutian, Shumagin, Fox and Pribilof islands; Atkan, spoken on Atka and Bering islands; and the now extinct Attuan dialect. The Pribilof Islands boast the highest number of active speakers of Aleutian.

In popular culture

In Neal Stephenson’s novel Snow Crash, the character Raven is an Aleut harpooner seeking revenge for the US’s nuclear testing on Amchitka. The Aleut tribes are also the subject of the Sue Harrison’s Ivory Carver Trilogy that includes Mother Earth Father Sky, My Sister the Moon, and Brother Wind, in addition to being the subject of Irving Warner’s 2007 historical novel about the Attuans held as prisoners of war in Japan, “The War Journal of Lila Ann Smith”.

The entry on Wikipedia is quite short, but the books listed on the bottom look like interesting summer readings. Maybe it would be a good idea to start gathering the titles of books and novels related with the subject of the blog, as I already do with the links. What do you thing?

Alaska Native Language Center

March 31, 2008 at 10:23 pm | Posted in Alaska, Language, Research | 1 CommentTags: ahtna, Alaska, aleut, alutiiq, center, central yup'ik, deg hit'an, dena'ina, eyak, fairbanks, gwich'in, haida, hän, holikachuk, iñupiaq, iingit, koyukon, Language, languages, map, Research, siberian yupik, tanacross, tanana, tsimshian, university, upper kuskokwim, upper tanana

As I told you in another post, I’m a linguist, a philologist to be accurate. So one of the main guidelines of my trip will be the study languages, probably. I suppose it is impossible not to be a bit influenced by that, and it is usually an interesting approach when traveling, as it offers a way of approaching people on the way. So, when on my last post I found out about language research concerning Arctic languages I decided to follow the thread. And it leads to Alaska Native Language Center:

Alaska Native Language Center

Mission and Goal

The Alaska Native Language Center was established by state legislation in 1972 as a center for research and documentation of the twenty Native languages of Alaska. It is internationally known and recognized as the major center in the United States for the study of Eskimo and Northern Athabascan languages. ANLC publishes its research in story collections, dictionaries, grammars, and research papers. The center houses an archival collection of more than 10,000 items, virtually everything written in or about Alaska Native languages, including copies of most of the earliest linguistic documentation, along with significant collections about related languages outside Alaska. Staff members provide materials for bilingual teachers and other language workers throughout the state, assist social scientists and others who work with Native languages, and provide consulting and training services to teachers, school districts, and state agencies involved in bilingual education. The ANLC staff also participates in teaching through the Alaska Native Language Program which offers major and minor degrees in Central Yup’ik and Inupiaq Eskimo at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. An AAS degree or a Certificate in Native Language Education is also available. The center continues to strive to raise public awareness of the gravity of language loss worldwide but particularly in the North. Of the state’s twenty Native languages, only two (Siberian Yupik in two villages on St. Lawrence Island, and Central Yup’ik in seventeen villages in southwestern Alaska) are spoken by children as the first language of the home. Like every language in the world, each of those twenty is of inestimable human value and is worthy of preservation. ANLC, therefore, continues to document, cultivate, and promote those languages as much as possible and thus contribute to their future and to the heritage of all Alaskans.

Alaska Native Languages

Aleut | Alutiiq | Iñupiaq | Central Yup’ik | Siberian Yupik | Tsimshian | Haida | lingit | Eyak | Ahtna | Dena’ina | Deg Hit’an | Holikachuk | Upper Kuskokwim | Koyukon | Tanana | Tanacross | Upper Tanana | Gwich’in | Hän

Classes and Degree Programs

There are 20 different Alaska Native languages: Aleut, Alutiiq (also called Aleut or Sugpiaq), Central Yup’ik Eskimo, St. Lawrence Island Eskimo, Inupiaq Eskimo, Tsimshian, Haida, Tlingit and Eyak and 11 Athabascan languages. These languages are becoming recognized as the priceless heritage they truly are.

Since the passage of the Alaska Bilingual Education Law in 1972 there has been a demand for teachers who can speak and teach these languages in the schools throughout the state where there are Native children. Professional opportunities for those skilled in these languages exist in teaching, research and cultural, educational and political development.

Central Yup’ik Eskimo is spoken by the largest number of people, and Inupiaq by the next largest. In these two languages major and minor curricula are now offered. Courses are also regularly offered in Kutchin (Gwich’in) Athabascan. For work in all other languages, individual or small-group instruction is offered under special topics. Thus there have frequently been instruction, seminars, and workshops also in Tlingit, Haida, St. Lawrence Island Eskimo, Aleut and Koyukon, comparative Eskimo and comparative Athabascan.

UAF is unique in offering this curriculum, which benefits also from the research staff and library of the Alaska Native Language Center.

Degree Programs Offered: Minor in Alaska Native Languages, B.A. or Minor in Iñupiaq or Yup’ik Eskimo, A.A.S. or Certificate in Native Language Education, M.A. in Applied Linguistics.

You can also check out their staff and publications. They also have an interesting “Resources” page, I will deal with it later.

First step: Alaska and Canada

March 12, 2008 at 1:17 am | Posted in Language, Maps, Naming | 3 CommentsTags: Alaska, aleut, Canada, eskimo, eskimo-aleut, ethnologue, inuit, inuktitut, inupiatu, Inupiatun, Yupik

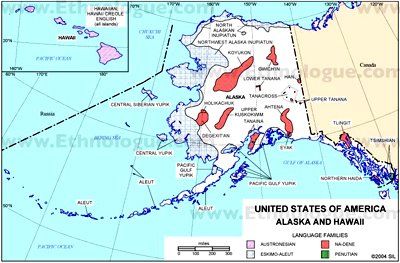

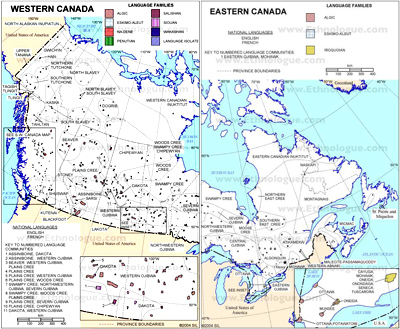

I’m working with Ethnologue trying to stablish the linguistic braches related with the North culture and lifestyle. I’ve made some interesting finds. Some language families spoken in Alaska and Canada are spoken also in Siberia, the North of Russia. That is exciting, as makes me wonder how it happened, so expect some future research into that direction.

Anyway, that is what I have found:

Alaska

In the United States of America there are 293,027,571 people. Population includes 1,900,000 American Indians, Inuits, and Aleut, not all speaking indigenous languages (1990 census). The National or official languages are Hawaiian (in Hawaii) and Spanish (in New Mexico). The number of languages listed for USA is 238. Of those, 162 are living languages, 3 are second language without mother-tongue speakers, and 73 are extinct. All the Inuit and Aleut languages are still alive.Aleut

[ale] 300 in the USA (1995 M. Krauss). Population total all countries: 490. Ethnic population: 2,000 (1995 M. Krauss). Western Aleut on Atka Island (Aleutian Chain); Eastern Aleut on eastern Aleutian Islands, Pribilofs, and Alaskan Peninsula. Also spoken in Russia (Asia). Dialects: Western Aleut (Atkan, Atka, Attuan, Unangany, Unangan), Eastern Aleut (Unalaskan, Pribilof Aleut). Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, AleutInupiatun, North Alaskan

[esi] Ethnic population: 8,000. Norton Sound and Point Hope, Alaska. Also spoken in Canada. Alternate names: North Alaskan Inupiat, Inupiat, “Eskimo”. Dialects: North Slope Inupiatun (Point Barrow Inupiatun), West Arctic Inupiatun, Point Hope Inupiatun, Anaktuvik Pass Inupiatun. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, InuitInupiatun, Northwest Alaska

[esk] 4,000 (1978 SIL). Speakers of all Inuit languages: 75,000 out of 91,000 in the ethnic group (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 8,000 (1978 SIL). Alaska, Kobuk River, Noatak River, Seward Peninsula, and Bering Strait. Alternate names: Northwest Alaska Inupiat, Inupiatun, “Eskimo”. Dialects: Northern Malimiut Inupiatun, Southern Malimiut Inupiatun, Kobuk River Inupiatun, Coastal Inupiatun, Kotzebue Sound Inupiatun, Seward Peninsula Inupiatun, King Island Inupiatun (Bering Strait Inupiatun). Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, InuitYupik, Central

[esu] 10,000 (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 21,000 (1995 M. Krauss). Nunivak Island, Alaska coast from Bristol Bay to Unalakleet on Norton Sound and inland along Nushagak, Kuskokwim, and Yukon rivers. Alternate names: Central Alaskan Yupik. Dialects: Kuskokwim Yupik (Bethel Yupik). There are 3 dialects, which are quite different. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Yupik, AlaskanYupik, Central Siberian

[ess] 1,050 in the USA (1995 Krauss). Population total all countries: 1,350. Ethnic population: 1,050 in USA (1995 Krauss). St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; Gambell and Savonga villages, Alaska. Also spoken in Russia (Asia). Alternate names: St. Lawrence Island “Eskimo”, Bering Strait Yupik. Dialects: Chaplino. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Yupik, SiberianYupik, Pacific Gulf

[ems] 400 (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 3,000 (1995 M. Krauss). Alaska Peninsula, Kodiak Island (Koniag dialect), Alaskan coast from Cook Inlet to Prince William Sound (Chugach dialect). 20 villages. Alternate names: Alutiiq, Sugpiak “Eskimo”, Sugpiaq “Eskimo”, Chugach “Eskimo”, Koniag-Chugach, Suk, Sugcestun, Aleut, Pacific Yupik, South Alaska “Eskimo”. Dialects: Chugach, Koniag. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Yupik, AlaskanCanada

In Canada there are 32,507,874 people, including 32,000 Inuit ethnic total (1993): 146,285 first-language speakers (1981 census). The National or official languages are English and French. Literacy rate: 96% to 99%. The number of languages listed for Canada is 89. Of those, 85 are living languages and 4 are extinct.

Inuktitut, Eastern Canadian

[ike] 14,000 (1991 L. Kaplan). Ethnic population: 17,500 (1991 L. Kaplan). West of Hudson Bay and east through Baffin Island, Quebec, and Labrador. Alternate names: Eastern Canadian “Eskimo”, “Eastern Arctic Eskimo”, Inuit. Dialects: “Baffinland Eskimo”, “Labrador Eskimo”, “Quebec Eskimo”. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, InuitInuktitut, Western Canadian

[ikt] 4,000 (1981). All Inuit first-language speakers in Canada 18,840 (1981 census). Ethnic population: 7,500 (1981 census). Central Canadian Arctic, and west to the Mackenzie Delta and coastal area, including Tuktoyaktuk on the Arctic coast north of Inuvik (but not Inuvik and Aklavik, and coastal area). Alternate names: Inuvialuktun. Dialects: Copper Inuktitut (“Copper Eskimo”, Copper Inuit), “Caribou Eskimo” (Keewatin), Netsilik, Siglit. Caribou dialect may need separate literature. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Inuit.Inupiatun, North Alaskan.Inupiatun, North Alaskan

[esi] Mackenzie delta region including Aklavik and Inuvik, into Alaska, USA. Alternate names: North Alaskan Inupiat, Inupiat, Inupiaq, “Eskimo”. Dialects: West Arctic Inupiatun (Mackenzie Inupiatun, Mackenzie Delta Inupiatun), North Slope Inupiatun. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Inuit

Here you have the wonderful Ethnologue maps as well:

Who they are: start dealing with naming

March 7, 2008 at 12:54 am | Posted in Naming | Leave a commentTags: Ainu, Alaska, aleut, Canada, chukchi, eskimo, evenki, finland, Greenland, husky, inuit, Japan, Kola peninsula, nenet, north america, norway, ostyak, russia, sami, sweden

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote the word ‘eskimo’ in an English composition. My teacher pointed to me that this was considered a politically incorrect and pejorative word. I had wrote it because, as a non-native English speaker, I liked how it sounded, and it was also pretty similar to the word I use in my own language, ‘esquimal’. Besides, in Linguistics there’s a group of languages called Eskimo-Aleut spoken in Canada, Alaska and Greenland, so I didn’t make me suspicious about being insensitive. But that worried me; it was a bad beginning for my trip starting naming contemptuously the people who I wanted to visit.

Basically -that’s pretty funny I guess – it’s a problem of terminology and naming, and now that I’ve started investigating it, it’s too much for me. I’m copying here everything I’ve founded in Dictionary.com, classified by geographical areas. Of course, opinions, corrections and comments are more than appreciated.

Alaska, Canada and Greenland

Eskimo

1.a member of an indigenous people of Greenland, northern Canada, Alaska, and northeastern Siberia, characterized by short, stocky build and light-brown complexion.

2.either of two related languages spoken by the Eskimos, one in Greenland, Canada, and northern Alaska, the other in southern Alaska and Siberia.Compare Inuit, Yupik.Usage note The name Inuit, by which the native people of the Arctic from northern Alaska to western Greenland call themselves, has largely supplanted Eskimo in Canada and is used officially by the Canadian government. Many Inuit consider Eskimo derogatory, in part because the word was, erroneously, long thought to mean literally “eater of raw meat.” Inuit has also come to be used in a wider sense, to name all people traditionally called Eskimo, regardless of local self-designations. Nonetheless, Eskimo continues in use in all parts of the world, especially in historical and archaeological contexts and in reference to the people as a cultural and linguistic unity. The term Native American is sometimes used to include Eskimo and Aleut peoples. See also Indian.Inuit

1.a member of the Eskimo peoples inhabiting northernmost North America from northern Alaska to eastern Canada and Greenland.

2.the language of the Inuit, a member of the Eskimo-Aleut family comprising a variety of dialects.Also, Innuit.

Also called Inupik.

Usage Note: The preferred term for the native peoples of the Canadian Arctic and Greenland is now Inuit, and the use of Eskimo in referring to these peoples is often considered offensive, especially in Canada. Inuit, the plural of the Inuit word inuk, “human being,” is less exact in referring to the peoples of northern Alaska, who speak dialects of the closely related Inupiaq language, and it is inappropriate when used in reference to speakers of Yupik, the Eskimoan language branch of western Alaska and the Siberian Arctic. See Usage Note at Eskimo.

Aleut

1.also, Aleutian. a member of a people native to the Aleutian Islands and the western Alaska Peninsula who are related physically and culturally to the Eskimos.

2.ahe language of the Aleuts, distantly related to Eskimo: a member of the Eskimo-Aleut family.Husky

1.Eskimo dog.

2.Siberian Husky.

3.Canadian Slang.

a. an Inuit.b. the language of the Inuit.

Usage note: Origin: 1870–75; by ellipsis from husky dog, husky breed; cf. Newfoundland and Labrador dial. Husky a Labrador Inuit, earlier Huskemaw, Uskemaw, ult. < the same Algonquian source as Eskimo.Norway, Sweden, Finland and Kola peninsula

Sami

1.A member of a people of nomadic herding tradition inhabiting Lapland.

2.Any of the Finnic languages of the Sami.Lapp

1.Also called Laplander . A member of a Finnic people of northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and adjacent regions.

2.Also called Lappish. any of the languages of the Lapps, closely related to Finnish.

Also called Sami.Siberia

Ostyak

1.a member of the nomadic Ugrian people living in northwestern Siberia (east of the Urals)

2.a Ugric language (related to Hungarian) spoken by the Ostyak [syn: Khanty]Chukchi

1.a member of a Paleo-Asiatic people of northeastern Siberia.

2.the Chukotian language of the Chukchi people, noted for having different pronunciations for men and women.Evenki

1.a member of a Siberian people living mainly in the Yakut Autonomous Republic, Khabarovsk territory, and Evenki National District in the Russian Federation.

2.the Tungusic language spoken by the Evenki.Samoyed

1.a member of a Uralic people dwelling in W Siberia and the far NE parts of European Russia.

2.Also, Samoyedic. a subfamily of Uralic languages spoken by the Samoyed people.Usage Note Siberian Mongolian people, 1589, from Rus. samoyed, lit. “self-eaters, cannibals” (the first element cognate with Eng. same, the second with O.E. etan “to eat”). The native name is Nenets. As the name of a type of dog (once used as a working dog in the Arctic) it is attested from 1889.

Nenets

1.A member of a reindeer-herding people of of extreme northwest Russia along the coast of the White, Barents, and Kara seas.

2.The Uralic language of this people.In both senses also called Samoyed.

Japan

Ainu

1.A member of an indigenous people of Japan, now inhabiting parts of Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands.

2.The language of the Ainu.

3.caucasoid people in Japan and eastern Russia, 1819, from Ainu, lit. “man.”

As it uses to happen, not only is the problem solved, but is it’s bigger. As far as I know, and though it’s not on the dictionary, ‘lapp’ and ‘lappish’ aren’t the right words, though I don’t know if it’s because its pejorative or just inadequate. I’ve put my head around Wikipedia, but the maps where so colorful and the words so complicated that I’ve decided that mt head was not prepared enough to hold out for such a terminological invasion. I’ll carry on another day.

Blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and comments feeds.