The Atlas of Canadian Languages

September 22, 2008 at 11:25 pm | Posted in Alaska, Canada, Language, Maps | 1 CommentTags: (Siouan) Dakota, Algonquian, athabaskan, cree, haida, inuktitut, Iroquoian, Kutenai, ojibway, Salish, Tlingit, tsimshian, Wakashan

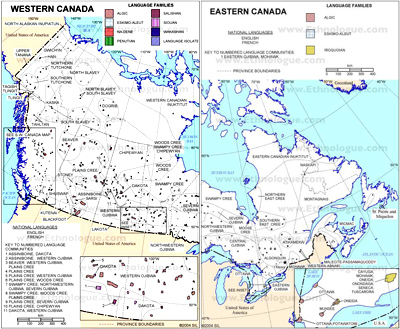

I arrived to this series of maps by the Atlas of Canada via the Alaska Native Languages Map blog. They offer information about the situation of languages in Canada, from three different perspectives: the linguistic group, the usage and the continuity:

Atlas of Canada

The linguistic group map

The current 50 languages of Canada’s indigenous peoples belong to 11 major language families – ten First Nations and Inuktitut. Canada’s Aboriginal languages are many and diverse, and their importance to indigenous people immense. This map shows the major aboriginal language families by community in Canada for the year 1996, and it is a part of a series of three maps that comprise Aboriginal Languages.

Some language families are large and strong in terms of viability, others small and vulnerable. The three largest families, which together represent 93% of persons with an Aboriginal mother tongue, are Algonquian (with 147 000 people whose mother tongue is Algonquian), Inuktitut (with 28 000) and Athabaskan (with 20 000). The other eight account for the remaining 7%. Tlingit, one of the smallest families, has a mere 145 people in Canada whose mother tongue is that language. Similar variations apply to individual languages – Cree, with a mother tongue population of 88 000, appears immense when compared with Malecite at 660.

Influence of Geography on the Size and Diversity of LanguagesGeography is an important contributor to the diversity, size and distribution of Aboriginal languages across Canada’s regions. Open plains and hilly woodlands, for example, are ideal for accommodating large groups of people. Because of the terrain, groups in these locations can travel and communicate with each other relatively easily, and often tend to spread over larger areas.

On the other hand, soaring mountains and deep gorges tend to restrict settlements to small pockets of isolated groups. British Columbia’s mountainous landscape with its numerous physical barriers was likely an important factor in the evolution of the province’s many separate, now mostly small, languages. Divided by terrain, languages such as Salish, Tsimshian, Wakashan, Haida, Tlingit and Kutenai could not develop as large a population base as the widely spread Algonquinian (particularly Cree and Ojibway) and the Athapaskan languages, whose homes are the more open central plains and eastern woodlands.

Geography can also influence the likelihood of a language’s survival. Groups located in relatively isolated regions, away from the dominant culture, face fewer pressures to abandon their language. They tend to use their own language in schooling, broadcasting and other communication services and, as a result, are likely to stay more self-sufficient. Communities living in Nunavut, Northwest Territories, the northern regions of Quebec and Labrador – the Inuit, Attikamek and Montagnais-Naskapi – are examples of such groups.

Because of their large, widely dispersed populations, the Algonquian languages account for the highest share of Aboriginal languages in all provinces except British Columbia and in the territories, ranging from 72% in Newfoundland to nearly 100% in the other Atlantic provinces. In both British Columbia and the Yukon, the Athapascan languages make up the largest share (26% and 80%, respectively), while Inuktitut is the most prominent Aboriginal language in the Northwest Territories and practically the only one in Nunavut. British Columbia, home to about half of all individual Aboriginal languages, is the most diverse in Aboriginal language composition. However, because of the small size of these language groups, the province accounts for only 7% of people with an Aboriginal mother tongue.

The ability mapThe Index of Ability compares the number of people who report being able to speak the language with the number who have that Aboriginal language as a mother tongue. The index has been compiled and mapped for each of the Aboriginal communities shown in the map Aboriginal Languages by Community, 1996. Relatively higher values of this index may suggest some degree of language revival. This map is part of a series of three maps that comprise Aboriginal Languages.

The INDEX OF ABILITY may be used to suggest some degree of language revival. The index of ability compares the number of people who report being able to speak the language with the number who have that Aboriginal language as a mother tongue (consult text Data and Mapping Notes for further information).

There are a number of factors which contribute to a language’s ability to survive. First and foremost is the size of the population with an Aboriginal mother tongue or home language. Since a large base of speakers is essential to ensure long-term viability, the more speakers a language has, the better its chances of survival. Indeed, Inuktitut, Cree and Ojibway – the three most flourishing languages – all boast over 20 000 people with an Aboriginal mother tongue. In contrast, endangered languages rarely have more than a few thousand speakers; often they have only a few hundred. For instance, the two smallest and weakest language groups, Kutenai and Tlingit, have mother tongue populations of 120 and 145 respectively.

To survive, a language must be passed on from one generation to the next. The most effective way of making this happen is to speak it in the home where children will learn it as their mother tongue. Spoken in the home, language is used as the working tool of everyday life. In contrast, when learned as a second language, it is often used in potentially limited situations, only as may be the case, for example, in immersion programs. There is, therefore, no equivalent to learning a language as a mother tongue. Unlike other minority language groups, Aboriginals cannot rely on new immigrants to maintain or increase their population of speakers. Consequently, passing on the language from parents to children is critical for the survival of all Aboriginal languages.

The continuity mapThe Index of Continuity measures language continuity, or vitality, by comparing the number of those who speak a given language at home to the number of those who learned the language as their mother tongue. The index has been compiled and mapped for each of the Aboriginal communities shown in the map Aboriginal Languages by Community, 1996. The lower the score, the greater the decline or erosion of language continuity. This map is part of a series of three maps that comprise Aboriginal Languages.

One way of measuring language continuity or vitality is the INDEX OF CONTINUITY. This index measures language continuity or vitality by comparing the number of those who speak an Aboriginal language at home to the number of those who learned the language as their mother tongue (consult text Data and Mapping Notes for further information).

Between 1981 and 1996, the index of continuity declined for all Aboriginal languages. Although the number of people reporting an Aboriginal mother tongue increased by nearly 24% between 1981 and 1996, the number of those who spoke an Aboriginal language at home grew by only 6%. As a result, for every 100 people with an Aboriginal mother tongue, the number who used an indigenous language most often at home declined from 76 to 65 between 1981 and 1996.

The index of continuity has some relationship to the ratings of languages as viable or endangered. Although most languages experienced a steady erosion in linguistic vitality during these years, endangered ones suffered the most. For example, the index of continuity for Salish languages fell from 35 in 1981 to only 12 by 1996. Tlingit and Kutenai, as languages most often spoken at home, had practically disappeared by the 1990s. Given that in 1996 there were only 120 people with a Kutenai mother tongue, it is not hard to see why there is a serious concern for the survival of this language. In contrast, although the continuity index dipped for the relatively strong Cree as well, it did so by considerably less: from 78 to 65. Although Inuktitut did experience a slight erosion in the early 1980’s, the past decade has seen its index stabilize at 84.

Groups that live in remote communities or in settlements with concentrated populations of indigenous speakers appear to find it easier to retain their language. Indeed, two such groups, on-reserve Registered Indians and the Inuit, show the highest indexes of language continuity among all groups: 80 and 85, respectively. In contrast, non-status Indians and Metis, who tend to live off-reserve, as well as off-reserve registered Indians have home-language-mother tongue ratios of 58, 50 and 40 respectively. This suggests a more pronounced state of language decline. Clearly, the off-reserve environment poses major threats to Aboriginal languages.

By 1996, these rates of language erosion resulted in strikingly different continuity levels for viable and endangered languages as a whole. For every 100 speakers with an Aboriginal mother tongue, an average of about 70 used an Aboriginal home language among viable groups, compared with 30 or fewer among endangered groups.

You can read data and mapping notes here.

What about Inuinnaqtun?

August 25, 2008 at 2:31 am | Posted in Canada, Language, Maps | 4 CommentsTags: Canada, dialect, inuinnaqtun, inuktitut, Language, map, nunavit

In the last post it arose a doubt about the languages of Nunavut, the Innu land in Canada. In their website they talk about Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun, as if they were separate languages. I googled it, and the Wikipedia says:

Inuinnaqtun is an indigenous language of Canada. It is related very closely to Inuktitut, and many people believe that Inuinnaqtun is only a dialect of Inuktitut. The governments of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut recognise Inuinnaqtun as an official language in addition to Inuktitut.

Inuinnaqtun is used primarily in the communities of Cambridge Bay and Kugluktuk in the western Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut. To a smaller extent it is also spoken in Gjoa Haven, Nunavut. Outside of Nunavut it is spoken in the hamlet of Ulukhaktok, Northwest Territories, where it is called Kangiryuarmiutun. It is written using the Latin alphabet.

Spoken in: Canada (Nunavut and Northwest Territories)

Total speakers: approximately 2,000

Language family: Inuit

I also found this in the Nunavut’s Languages Comissioner:

Inuktitut/Inuinnaqtun is the largest language group in Nunavut. Seventy percent of Nunavummiut speak Inuktitut as their first language.

Inuktitut is divided up into a number of different dialects, including Inuinnaqtun, which is spoken in the western-most parts of the territory. Inuinnaqtun uses Roman orthography, rather than syllabics.

This last page has a lot of material, I will dig into it later on!

Tunngasugitti, and Welcome to Nunavut!

August 24, 2008 at 8:35 pm | Posted in Canada, History, Organization | 1 CommentTags: autonomy, Canada, inuinnaqtun, inuktitut, nunavut

More facts about Nunavut from a PDF document of their site.

GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT

Tunngasugitti, and Welcome to Nunavut!

Our LandNunavut (the Inuktitut word for “our land”) was created April 1, 1999 as a result of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement. For millennia a major Inuit homeland, Nunavut today is a growing society that blends the strength of its deep Inuit roots and traditions with a new spirit of diversity.

It is a territory that spans the two million square kilometres of Canada extending north and west of Hudson’s Bay, above the tree line to the North Pole. With landscapes that range from the flat muskeg of the Kivalliq to the towering mountain peaks and fiords of North Baffin, it is a Territory of extraordinary variety and breathtaking beauty.

With a median age of 22.1 years, Nunavut’s population is the youngest in Canada. It is also one of the fastest growing; the 2001 population of just under 29,000 represents an increase of eight per cent in only five years. Inuit represent about 85 percent of the population, and form the foundation of the Territory’s culture. Government, business and day-to-day life are shaped by Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, the traditional knowledge, values and wisdom of Nunavut’s founding people.

Our 26 communities range in size from tiny Bathurst Inlet (population 25) to Iqaluit, the capital (population almost 6,500). Grise Fiord, the northernmost settlement, lies at 78 degrees north: the hamlet of Sanikiluaq in the Belcher Islands is actually further south than Ontario’s northern border. None are accessible by road or rail; everything, from people to fuel to food, arrives by plane or sealift. This physical isolation accounts for the highest cost of living in Canada, reflected in prices throughout the Territory.

The largest employer in Nunavut is government – federal, territorial, and municipal. But new jobs are rapidly emerging in the mining and resource development sectors. Important growth is also occurring in the tourism sector, in fisheries, and in Inuit art such as carvings and prints.

The realization of Nunavut’s full economic potential will, in part, be contingent upon the improvement of the territory’s infrastructure. Existing housing, sewage and waste management, transportation and telecommunications systems are already stretched beyond their limits, and will come under even greater pressure from Nunavut’s growing population.

With four languages (Inuktitut, Inuinnaqtun, English and French), an area one-fifth the size of Canada, and a population density of one person per 70 km sq., the creation of Nunavut has called for innovative approaches to the delivery of virtually every aspect of government programs and services.

From health to education, from justice to the structure of the Legislative Assembly, the institutions and structures that define Nunavut are designed to meet the needs of a unique people in a unique land.

The challenges are many; but in partnership with Canada, and building on the strength and energy of its people, Canada’s newest Territory looks to the future with confidence and hope.

So it seems that I have been missing one language, Inuinnaqtun. And I do not know if there are more non-official languages. And I also have to look for more information about the Cree people, I do not know if they share the same territories or not. So homework for the next days!

Produced by Nutaaq

August 5, 2008 at 12:34 pm | Posted in Canada, Education, Organization | Leave a commentTags: Canada, cree, documenrary, DVD, inuktitut, media, nutaaq, quebec, serie, television, tv

Last week I found a production company settled down in Québec, Canada, called Nutaaq. As they explain, they are specialized on multi-cultural and indigenous subjects. This is quite interesting, isn’t it?

Nutaaq Média

Nutaaq Média, Inc. was incorporated in 1991 with the goal of producing both independent and sponsored film, video and interactive media projects.

Although most of Nutaaq productions concern the Arctic or northern issues, Nutaaq has also shot many projects in southern Canada, as well as one project in South America. Our multi-cultural experience is indeed one of our great strengths.

Nutaaq Média represents many years of production experience which allow it to create broadcast programming intended for a mass audience or sponsored projects tailored to a specific few.

Working with a team of talented professionals and state of the art facilities for digital non-linear editing and multi-media authoring, Nutaaq Média produces effective multi-media, sponsored or broadcast programming tailored to client and audience needs in whichever languages are required. In the past, Nutaaq has produced programs in French, English, Inuktitut and Cree, Chinese, Japanese, Russian, Spanish, German and Italian. Nutaaq can also title and sub-title programs in any language. We also do closed captioning.

Recent Productions

Finding My Talk:A Journey through Aboriginal Languages This one hour documentary follows the journey of Cree filmmaker Paul M. Rickard as he searches for his own language roots and discovers the tireless efforts of many individuals who are promoting, reviving and preserving the use of Aboriginal languages within their communities. Distributed by Mushkeg Media Inc.

Broken Promises: The High Arctic Relocation In the summer of 1953, the Canadian government relocated seven Inuit families from Northern Québec to the High Arctic. They were promised an abundance of game and fish – in short, a better life. The government assured the Inuit that if things didn’t work out, they could return home after two years. Two years later, another 35 people joined them. It would be thirty years before any of them saw their ancestral lands again. Distributed by Nutaaq and National Film Board of Canada.

Nunavik Heritage CD-ROM The photographs reflect the life and people of Northern Québec (Nunavik) from the 1880’s till the present. The flexibility of the CD-ROM software allows the images to be organized and retrieved by thematic categories such as specific individuals or families, geographical locations, time periods, historical events or photograph contents. The disc design maximizes user interaction and allows images to be printed or incorporated into other documents. Distributed by Avataq Cultural Institute.

Running the Midnight Sun To their friends they’re eccentric, to the Inuit they’re bizarre, but they consider themselves just ordinary people who like to push themselves to the limit. They are ultra runners. Once a year, under a sun that never sets, they gather from all over North America to challenge an 84 kilometer gravel road located 700 kilometers above the Arctic Circle. Distributed by Nutaaq.

North to Nowhere: Quest for the Pole In North to Nowhere, nine adventurers from five countries attempt the Polar trek. They include Shinzi Kazama, a motorcyclist from Japan; Pam Flowers, a ninety pound dogsledder from Alaska; Nicholas Hulot and Hubert de Chevigny, ultra-light pilots from France and Dick Smith, an Australian helicopter pilot. As well, a planeload of American tourists fly to the Pole for a very expensive one hour photo opportunity. No Distributer (unavailable).

They produced some documentaries in Inuktitut and Cree, this is interesting. I contacted them since living in Barcelona it is impossible to watch their programs, but the only option was to buy them, and that was really expensive for me too! I may wait when a relative or friend travel there, to see if they find something!

Greenland tactile maps

May 12, 2008 at 5:34 pm | Posted in Greenland, Maps | 1 CommentTags: geography, Greenland, inuit, inuktitut, knowledgment, map, wood

After a pretty long break, I received a push and started again. A friend sent me an entry from a blog talking about the relieve maps that the Inuit people carved in wood sticks.

Traditionally linked to the sea and for that expert sailors, they had a strong knowledgement of the intricate Greenland’s coasts. Added to this, they had a different way to give expression to this knowledgment. They carved on wood the pattern and shape of the coast, as you see in the picture:

Font: Colleen Morgan

For more information, check this site and this other one.

Chatting in Inuktitut

April 9, 2008 at 9:36 pm | Posted in Canada, Language | Leave a commentTags: affairs, Canada, glossary, indian, inuktitut, Language, northern, sentences, speak, words

Have you ever wonder how to confess your passion for pizza even if you are in Greenland? Now you can speak openly about it even eating fresh fish inside an igloo thanks to this short glossary offered by the Indian and Northern Affairs of Canada:

I belong to the _______ Nation.

I bet you to go there an say “no waaaay” if they ask you if you are missing your warm hometown next summer 😉

Second step: Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland)

April 3, 2008 at 10:05 pm | Posted in Language, Maps, Naming | 1 CommentTags: denmark, ethnologue, Greenland, inuit, inuktitut, kalaallit nunaat, Language, sociolinguistics

It has been a while since my entry about the maps in Ethnologue, when I posted the information concerning Alaska and Canada. To be honest, the I was thinking that it would be difficult to find information for my project. But I have been jumping from one site to another one, and I had almost forget about this basic step. So here I go; this time, the Ethnologue report for Greenland, or, rather, Kalaallit Nunaat:

Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland)

The total population is 56.384. National or official languages: Greenlandic Inuktitut, Danish. Affiliated with Denmark; home rule since 1979. Literacy rate: 93%. The number of languages listed for Greenland is two: Danish and Greenlandic Inuktitut. Of those, both are living languages.

Inuktitut, Greenlandic

[kal] 47,800 in Greenland (1995 Krauss). Population includes 3,000 East Greenlandic, 44,000 West Greenlandic, 800 North Greenlandic. Population total all countries: 54,800.Greenland. About 80 communities of populations over 10. Also spoken in Denmark. Alternate names: Greenlandic, Kalaallisut. Dialects: West Greenlandic, East Greenlandic, “Polar Eskimo” (North Greenlandic, Thule Inuit). Dialects border on being different languages (M. Krauss 1995). Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Inuit.

I couldn’t find the map for Greenland in Ethnologue, maybe it doesn’t exist…

Locating Newfoundland and Labrador

March 21, 2008 at 9:39 pm | Posted in Language, Maps | Leave a commentTags: Canada, census, cree, History, Innu, innu-aimun, inuktitut, labrador, Language, montaignais, naskapi, newfoundland, peninsula, statistics

I will continue with the people in Canada. Today, talking with some workmates, this topic has come out, and they have been telling me some things. The situation it is still not clear, but now I have more clues to keep searching. They told me that it had hit the headlines that ten years ago Canada gave some authonomy to one of its provinces, traditionally indigenous. Since I have no idea about it, I started looking for it at the Wiki:

Concerning Innu’s land, in 1869, Newfoundland decided in an election to remain a British territory, over concerns that central Canada would dominate taxation and economic policy. In 1907, Newfoundland and Labrador acquired dominion status. However, in 1933, the government of Newfoundland fell and during World War II, Canada took charge of Newfoundland’s defence. Following World War II, Newfoundland’s status was in question. In a narrow majority, the citizens of Newfoundland and Labrador voted for confederation in a 1948 referendum. On March 31, 1949, Newfoundland and Labrador became Canada’s tenth and final province.

Geographically, the province consists of the island of Newfoundland and the mainland Labrador, on Canada’s Atlantic coast. While the name “Newfoundland” is derived from English as “New Found Land” (a translation from the Latin Terra Nova), Labrador comes from the Portuguese lavrador, a title meaning “landholder” held by Portuguese explorer of the region, João Fernandes Lavrador.

As of October, 2007, the province’s population is estimated to be 507,475. Newfoundland has its own dialects of the English, French, and Irish languages. The English dialect in Labrador shares much with that of Newfoundland. Furthermore, Labrador has its own dialects of Innu-aimun and Inuktitut.

The 2006 census returns showed a population of 505,469. Of the 499,830 singular responses to the census question concerning ‘mother tongue’ the languages most commonly reported were:

| 1. | English | 488,405 | 97.7% |

| 2. | French | 1,885 | 0.4% |

| 3. | Montagnais-Naskapi | 1,585 | 0.3% |

| 4. | Chinese | 1,080 | 0.2% |

| 5. | Spanish | 670 | 0.1% |

| 6. | German | 655 | 0.1% |

| 7. | Inuktitut | 595 | 0.1% |

| 8. | Urdu | 550 | 0.1% |

| 9. | Arabian | 540 | 0.1% |

| 10. | Dutch | 300 | 0.1% |

| 11. | Russian | 225 | ~ |

| 12. | Italian | 195 | ~ |

The website of the Newfoundland and Labrador Government offers some information, as well as an interesting section that focuses on Labrador’s aboriginals. But you will have to wait for the next chapters for that 🙂

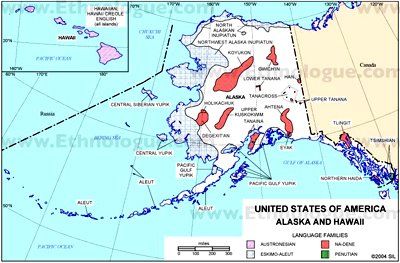

First step: Alaska and Canada

March 12, 2008 at 1:17 am | Posted in Language, Maps, Naming | 3 CommentsTags: Alaska, aleut, Canada, eskimo, eskimo-aleut, ethnologue, inuit, inuktitut, inupiatu, Inupiatun, Yupik

I’m working with Ethnologue trying to stablish the linguistic braches related with the North culture and lifestyle. I’ve made some interesting finds. Some language families spoken in Alaska and Canada are spoken also in Siberia, the North of Russia. That is exciting, as makes me wonder how it happened, so expect some future research into that direction.

Anyway, that is what I have found:

Alaska

In the United States of America there are 293,027,571 people. Population includes 1,900,000 American Indians, Inuits, and Aleut, not all speaking indigenous languages (1990 census). The National or official languages are Hawaiian (in Hawaii) and Spanish (in New Mexico). The number of languages listed for USA is 238. Of those, 162 are living languages, 3 are second language without mother-tongue speakers, and 73 are extinct. All the Inuit and Aleut languages are still alive.Aleut

[ale] 300 in the USA (1995 M. Krauss). Population total all countries: 490. Ethnic population: 2,000 (1995 M. Krauss). Western Aleut on Atka Island (Aleutian Chain); Eastern Aleut on eastern Aleutian Islands, Pribilofs, and Alaskan Peninsula. Also spoken in Russia (Asia). Dialects: Western Aleut (Atkan, Atka, Attuan, Unangany, Unangan), Eastern Aleut (Unalaskan, Pribilof Aleut). Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, AleutInupiatun, North Alaskan

[esi] Ethnic population: 8,000. Norton Sound and Point Hope, Alaska. Also spoken in Canada. Alternate names: North Alaskan Inupiat, Inupiat, “Eskimo”. Dialects: North Slope Inupiatun (Point Barrow Inupiatun), West Arctic Inupiatun, Point Hope Inupiatun, Anaktuvik Pass Inupiatun. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, InuitInupiatun, Northwest Alaska

[esk] 4,000 (1978 SIL). Speakers of all Inuit languages: 75,000 out of 91,000 in the ethnic group (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 8,000 (1978 SIL). Alaska, Kobuk River, Noatak River, Seward Peninsula, and Bering Strait. Alternate names: Northwest Alaska Inupiat, Inupiatun, “Eskimo”. Dialects: Northern Malimiut Inupiatun, Southern Malimiut Inupiatun, Kobuk River Inupiatun, Coastal Inupiatun, Kotzebue Sound Inupiatun, Seward Peninsula Inupiatun, King Island Inupiatun (Bering Strait Inupiatun). Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, InuitYupik, Central

[esu] 10,000 (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 21,000 (1995 M. Krauss). Nunivak Island, Alaska coast from Bristol Bay to Unalakleet on Norton Sound and inland along Nushagak, Kuskokwim, and Yukon rivers. Alternate names: Central Alaskan Yupik. Dialects: Kuskokwim Yupik (Bethel Yupik). There are 3 dialects, which are quite different. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Yupik, AlaskanYupik, Central Siberian

[ess] 1,050 in the USA (1995 Krauss). Population total all countries: 1,350. Ethnic population: 1,050 in USA (1995 Krauss). St. Lawrence Island, Alaska; Gambell and Savonga villages, Alaska. Also spoken in Russia (Asia). Alternate names: St. Lawrence Island “Eskimo”, Bering Strait Yupik. Dialects: Chaplino. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Yupik, SiberianYupik, Pacific Gulf

[ems] 400 (1995 M. Krauss). Ethnic population: 3,000 (1995 M. Krauss). Alaska Peninsula, Kodiak Island (Koniag dialect), Alaskan coast from Cook Inlet to Prince William Sound (Chugach dialect). 20 villages. Alternate names: Alutiiq, Sugpiak “Eskimo”, Sugpiaq “Eskimo”, Chugach “Eskimo”, Koniag-Chugach, Suk, Sugcestun, Aleut, Pacific Yupik, South Alaska “Eskimo”. Dialects: Chugach, Koniag. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Yupik, AlaskanCanada

In Canada there are 32,507,874 people, including 32,000 Inuit ethnic total (1993): 146,285 first-language speakers (1981 census). The National or official languages are English and French. Literacy rate: 96% to 99%. The number of languages listed for Canada is 89. Of those, 85 are living languages and 4 are extinct.

Inuktitut, Eastern Canadian

[ike] 14,000 (1991 L. Kaplan). Ethnic population: 17,500 (1991 L. Kaplan). West of Hudson Bay and east through Baffin Island, Quebec, and Labrador. Alternate names: Eastern Canadian “Eskimo”, “Eastern Arctic Eskimo”, Inuit. Dialects: “Baffinland Eskimo”, “Labrador Eskimo”, “Quebec Eskimo”. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, InuitInuktitut, Western Canadian

[ikt] 4,000 (1981). All Inuit first-language speakers in Canada 18,840 (1981 census). Ethnic population: 7,500 (1981 census). Central Canadian Arctic, and west to the Mackenzie Delta and coastal area, including Tuktoyaktuk on the Arctic coast north of Inuvik (but not Inuvik and Aklavik, and coastal area). Alternate names: Inuvialuktun. Dialects: Copper Inuktitut (“Copper Eskimo”, Copper Inuit), “Caribou Eskimo” (Keewatin), Netsilik, Siglit. Caribou dialect may need separate literature. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Inuit.Inupiatun, North Alaskan.Inupiatun, North Alaskan

[esi] Mackenzie delta region including Aklavik and Inuvik, into Alaska, USA. Alternate names: North Alaskan Inupiat, Inupiat, Inupiaq, “Eskimo”. Dialects: West Arctic Inupiatun (Mackenzie Inupiatun, Mackenzie Delta Inupiatun), North Slope Inupiatun. Classification: Eskimo-Aleut, Eskimo, Inuit

Here you have the wonderful Ethnologue maps as well:

Blog at WordPress.com.

Entries and comments feeds.